Understanding Colorado’s Child Abuse Laws Can Be Challenging- 18-6-401

By H. Michael Steinberg Colorado Criminal Defense Lawyer

Introduction

The nightmare of a child’s criminal charge is compounded when, as a parent, you are also criminally charged for your child’s acts.

This article examines, not only the scenario of legal responsibility as a parent or legal guardian for your child’s criminal acts, but also examines some of the key and critical issues that surround cases of alleged child abuse in Colorado.

While I have written on the subject of child abuse before, this article, after reviewing Colorado’s child abuse laws, focuses on some of the more complex legal issues in child abuse cases.

A Recent Colorado Case Illustrates a Parent’s Responsibility for the Crimes of that Parents Child

In 2021, a Colorado mother was prosecuted for felony child abuse for negligently causing the death of her three-year-old daughter even though the accused mother was outside smoking a cigarette when her daughter child was shot and killed by her seven-year-old brother.

The three-year-old and her brother were playing “swords” inside the home when the boy found and picked up a shotgun that was unsecured and loaded and lying on the couch. Ruby, the three-year-old, had picked up a broomstick to engage her brother in the sword fight game. In response, her brother found the12 gauge shotgun and “pushed the button” discharging the shotgun and killing his little sister.

The mother, twenty-four-year-old Michaela Harman, had loaded her shotgun and brought it downstairs to the main family room leaving it there unsecured. She was charged with negligent child abuse resulting in death, Her remaining children were placed into the custody of Human Services.

At the time of her daughter’s death, Harman was outside smoking a cigarette. She hurried inside when she heard the shot. She realized too late that she had left the loaded shotgun near the couch before heading to bed the previous night. (She state that she was worried about potential intruders trying to break into her home over the past few days. Police had been called to the home each time but had not found evidence of any foul play.)

Determining Criminal Responsibility for an Alleged Act of Child Abuse is …Complex

In the 2021 case discussed above, the theory of criminal responsibility for holding the defendant – mother responsible for the acts of her son was founded on a charge of negligent child abuse resulting in death. In this case, the theory for prosecuting the case was the negligent act of leaving a loaded shotgun in the family home where the child could find and use it.

This article primarily examines, not whether an alleged crime is an act of child abuse (addressed in other articles), but determining how a parent or guardian can be held criminally responsible for child abuse.

The Duty of A Parent Caregiver to Protect Children

Colorado law provides that parents (which includes legal guardians and caregivers) have a legal duty to prevent the abuse of their children. That duty of care is based on the special relationship between parents and their children. Every parent is legally and morally tasked to provide for the safety of their child. While there are many such special relationships under criminal law, the relationship between a parent and a child exemplifies the kind of a special relationship where the duty to protect is imposed.

A failure to protect a child a person legally obligated to protect can be punishable by law as child abuse. Colorado’s child abuse laws are among the most serious and complex in the Colorado criminal code.

Colorado’s Child Abuse Law – Section 18-6-401

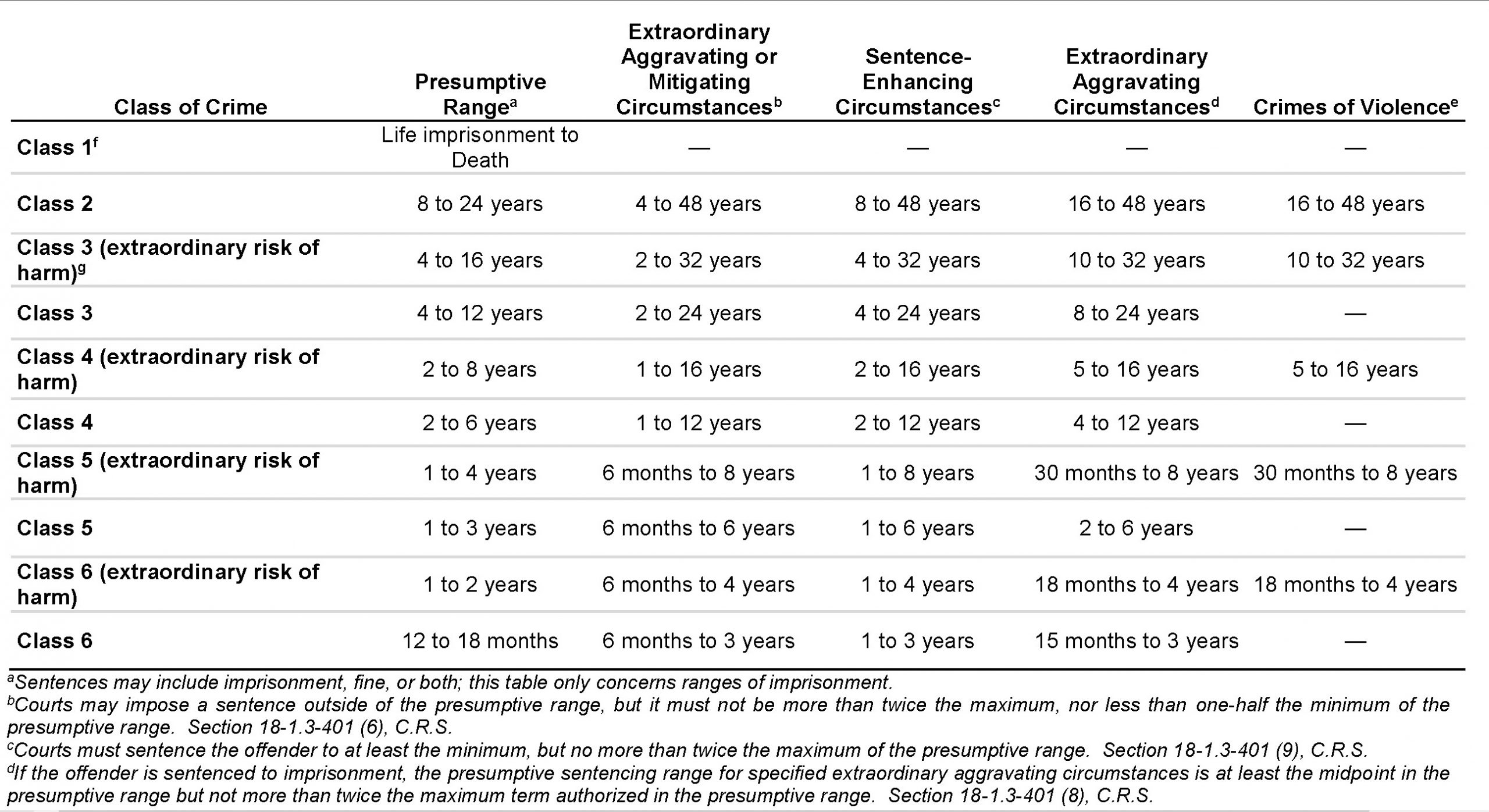

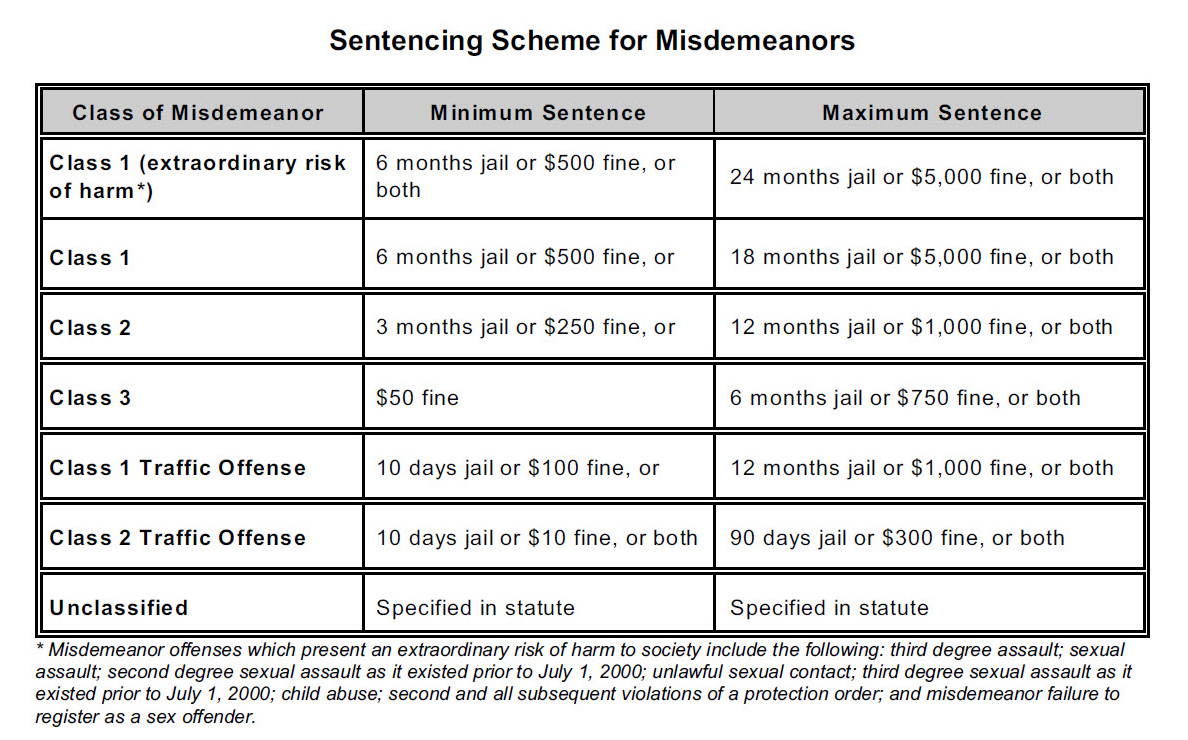

Colorado’s felony and misdemeanor child abuse laws have enhanced penalties that are categorized under extraordinary risk crimes that are subject to the modified and more severe presumptive sentencing range specified in the charts below. (click to enlarge).

To properly analyze a criminal charge of child abuse in Colorado, a comprehensive understanding of the structure of the Colorado child abuse law is key. The various ways the crime of child abuse can be charged and the possible penalties are key to understanding what one is facing if charged with child abuse.

The Overarching Definition of Child Abuse

Child abuse as defined in the words of Section 18-4-401 is as follows:

(1)(a) A person commits child abuse if such person:

- causes an injury to a child’s life or health, or

- permits a child to be unreasonably placed in a situation that poses a threat of injury to the child’s life or health, or

- engages in a continued pattern of conduct that results in malnourishment, lack of proper medical care, cruel punishment, mistreatment, or

- an accumulation of injuries,

- that ultimately results in the death of a child or serious bodily injury to a child.

A child is defined as a person under the age of sixteen years.

A Voluntary Act Combined with a Certain Mental State

Under Colorado law, a crime is committed when the defendant has committed a voluntary act (the actus reus) prohibited by law, together with a specific state of mind (the mens rea).

Actus reus is a “guilty act,” and refers to an overt act in furtherance of a crime. Mens rea means to have “a guilty mind.”

A“voluntary act” means an act performed consciously as a result of effort or determination.

Proof of a voluntary act alone is insufficient to prove that the accused had the required state of mind to have committed a criminal act of child abuse.

The state of mind (the mens rea) is as much an element of the crime as the act itself and must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt, either by direct or circumstantial evidence.

Colorado child abuse laws break down acts of child abuse into combinations of injuries to the child coupled with the relevant and provable mental state.

Once the nature of an injury is understood, Colorado’s child abuse law requires a further analysis of the mental state of the perpetrator at the time of the alleged infliction of that injury.

The possible penalty is then enhanced or lowered depending on the mental state of the accused at the time he or she inflicted the injury.

Review: A Voluntary Act Coupled with a Requisite Mental State

In analyzing a Colorado child abuse charge, (assuming for these purposes a voluntary act), there are basically two major components:

I. The Mental State of the Defendant: (the “mens rea” or the mindset of the accused at the time of the injury), and

II. The Injury Sustained by the Victim caused by the voluntary act of the accused.

I. The Mental State (The “Mens Rea” or the Mind Set of the Accused at the Time of the Injury).

The four mental states for crimes under Colorado law are, from highest to lowest:

Acting With Intent: A person acts “intentionally” or “with intent” when his or her conscious objective is to cause the specific result proscribed by the statute defining the offense. It is immaterial whether the result actually occurred.

Acting “Knowingly” or “Willfully” with respect to conduct or to a circumstance described by a statute defining an offense means he or she is aware that his conduct is of such nature or that such circumstance exists. A person acts “knowingly” with respect to a result of his conduct when he is aware that his conduct is practically certain to cause the result.

Acting “Recklessly” means consciously disregarding a substantial and unjustified risk that a result will occur or that a circumstance exists.

Acting “With Criminal Negligence” means through a gross deviation from the standard of care that a reasonable person would exercise, that person fails to perceive a substantial and unjustified risk that a result will occur or that a circumstance exists.

II. The Injury Sustained by the Victim

A. If Death Results from the Act of Child Abuse

Mental State: Knowingly or Recklessly

If the person acts knowingly or recklessly and the child abuse results in death to the child, it is a class 2 felony.

Mental State: Criminal Negligence

If the person acts with criminal negligence and the child abuse results in death to the child, it is a class 3 felony.

B. If Serious Bodily Injury Results from the Act of Child Abuse

Mental State: Knowingly or Recklessly

If the person acts knowingly or recklessly and the child abuse results in serious bodily injury to the child, it is a class 3 felony.

Mental State: Criminal Negligence

If the person acts with criminal negligence and the child abuse results in serious bodily injury to the child, it is a class 4 felony.

C. If Any Other Injury Results from the Act of Child Abuse

Mental State: Knowingly or Recklessly

If the person acts knowingly or recklessly and the child abuse results in any injury other than serious bodily injury, it is a class 1 misdemeanor

Mental State: Criminal Negligence

If the person acts with criminal negligence and the child abuse results in any injury other than serious bodily injury to the child, it is a class 2 misdemeanor;

D. If No Death or Injury Results from the Act of Child Abuse

Mental State: Knowingly or Recklessly

If the person acts knowingly or recklessly and there is no injury, it is a class 2 misdemeanor;

Mental State: Criminal Negligence

If the person acts with criminal negligence is a class 3 misdemeanor;

Sentence Enhancer One – Child Victims Under Twelve Years of Age

Child Abuse Death of the Child, Knowing, Position of Trust – First Degree Murder

When a person knowingly causes the death of a child who has not yet attained twelve years of age and the person committing the offense is one in a position of trust with respect to the child, such person knowingly commits the crime of murder in the first degree.

The penalty is enhanced to a Class 1 Felony – and the penalty is life imprisonment.

Sentence Enhancer Two – The Effect of a Previous Conviction – Position of Trust – Plus Factual Aggravators

A person who has previously been convicted of child abuse under Colorado law or a crime of child abuse in any other state, the United States, or any territory commits a class 5 felony and:

That person was in a position of trust with respect to a child if at the time of an act of child abuse such as an injury (or even in the absence of an injury).

[A person in a position of trust includes, but is not limited to, a child’s:

Parent or foster parent,

Legal guardian,

Teacher or school counselor,

Daycare workers or babysitters, and

Medical or other health care professional.]

OR,

If the caregiver has a prior conviction for child abuse

AND:

Participated in a continued pattern of conduct that resulted in the child’s malnourishment or failed to ensure the child’s access to proper medical care;

Participated in a continued pattern of cruel punishment or unreasonable isolation or confinement of the child;

Made repeated threats of harm or death to the child or to a significant person in the child’s life, which threats were made in the presence of the child;committed a continued pattern of acts of domestic violence…in the presence of the child; or

Participated in a continued pattern of extreme deprivation of hygienic or sanitary conditions in the child’s daily living environment.

The crime may be enhanced from a misdemeanor to a class 5 felony even in the absence of physical injury.

The Difficulties of Proving the Crime of Child Abuse

Identifying the party or parties responsible for an act of child abuse case can be a very difficult task for Colorado law enforcement. Because child abuse occurs most frequently in the privacy of the home and can involve multiple caregivers, such as both of the parents of the child, conclusive evidence of causation of the alleged victim’s injuries may be factually ambiguous and therefore problematic for a prosecutor at trial.

It can be difficult to identify the person the party who actively caused physical harm to the child. If there is a second person in the home who is aware of the abuse and may even have passively permitted it, determining the relative culpability of the responsible parties can sometimes be nearly impossible.

Establishing the target of the prosecution, the actual “abuser,” and constructing the required direct or circumstantial evidence of the abuse, such as an eyewitness or the collection of forensic evidence exposes one of the primary weaknesses in these prosecutions.

It is important to remember that the burden of proof is always on the state to prove where or exactly how the crime took place. While forensic evidence can assist in an attempt to prove that an injury was non-accidental trauma (NAT), there are limitations on that how far such evidence will take an investigation of child abuse.

Non-Accidental Trauma (NAT) – Prosecuting Colorado Child Abuse Cases – Establishing Guilt

Non-accidental trauma (NAT) is an injury purposefully inflicted upon a child. Where there are two parents both at home jointly caring for a child, if there are no cooperating eyewitnesses and the child is pre-verbal (or otherwise too young or unable to testify), the person responsible for the mechanism of the injury may be difficult to identify and to isolate.

Often the forensic evidence is at best ambiguous on the key issue of the identification of which of the two caregivers was responsible for the injury. If neither party agrees to make a statement against the other, it is often impossible to prove who was the “active” and who, in exercising their right to remain silent may be viewed as the “passive” abuser by law enforcement.

The Right to Remain Silent Under the Fifth Amendment in Colorado Child Abuse Cases

The Fifth Amendment provides, in relevant part,

“No person … shall be compelled in an criminal case to be a witness against himself ….”

In child abuse cases, as in all criminal prosecutions, a prosecutor is not permitted to draw adverse inferences on a parent or other caregiver’s exercise of their right to remain silent when questioned about suspected child abuse.

Under our system of justice, it is not whether the defendant committed the acts of which he is accused, it is whether the state has carried its burden to prove its allegations while protecting a defendant’s individual rights.

The United States system of criminal justice is a rights-based accusatorial system. It is a system built upon protecting against a conviction of the innocent and limiting the authority of the government.

“Active” and “Passive” Child Abusers – The Duty to Testify to a Crime of Child Abuse

Recall Colorado’s definition of child abuse:

(1)(a) A person commits child abuse if such person:

causes an injury to a child’s life or health, or

permits a child to be unreasonably placed in a situation that poses a threat of injury to the child’s life or health, or

Let’s return to the Michaela Harman case above. As a mother charged with the safety of her children, Ms. Harman was tasked with the well-recognized legal duty to provide for the safety of her children.

The more difficult question posed here is this, if a parent or caregiver who is an eyewitness to an act or a pattern of child abuse by the active abuser’s actions, exercises their right to remain silent, can the prosecutor proceed, in a case of clear non-accidental trauma, using an accomplice liability theory of prosecution by criminally charging the “silent” parent for not cooperating in the investigation?

The answer is no. A passive parent’s “mere presence” during the relevant time period in question (when an act of child abuse occurs) is insufficient to establish criminal liability without more.

A case cannot be made that the passive parent is independently criminally liable because that parent was present when the other parent caused an injury and did not intervene.

If the theory of prosecution in a Colorado child abuse case rests solely on the inference that because one of the parents failed to fulfill the duty to protect that child victim, that prosecution most likely will not lie.

Prosecuting Child Abuse Under the legal Theory of Complicity – “Accomplice Liability”

Consider this fact pattern. Both parents are at home together and responsible for the care of a child at a time when their child sustains non-accidental injuries but only one parent has inflicted injuries on the child. The other parent is present but does nothing to either injure the child or to protect the child from the injuries.

Under these facts, it may be possible for both defendants to be found guilty of child abuse under the legal theory of prosecution called accomplice liability (aiding and abetting – because of the inherent duty of parents to provide for the safety and welfare of their children.). However, to succeed under this theory of prosecution, the state must prove not only the identity of the active abuser but of the passive abuser using any evidence from the investigation.

As a matter of law, depending on the facts, it is possible for a case to be prosecuted based on the failure of a parent to take affirmative action to prevent harm to his or her child. The problem in this context is the quantum of evidence available to the police – the sufficiency of the evidence.

The evidence must prove that both parents were present, both were aware of the mechanism of the injury and each assisted, aided and abetted, the other in some way in bringing the injury about.

Unless the prosecution can prove exactly when the child abuse occurred and/or who was present, accomplice liability usually cannot be sustained. While it may be clear in such a case that someone committed an act of child abuse, unless both defendants can somehow be proven guilty, normally neither can be convicted.

Accomplice liability is based on the defendant’s knowledge or awareness of the risks. If the state can prove that a parent knows that his or her child is in a dangerous situation and fails to take action to protect the child and therefore at least passively “assisted” in the facilitation of the offense theoretically that parent may be convicted of aiding and abetting that assault solely on the ground that the parent was present when the child was assaulted and failed to take reasonable steps to prevent the assault.

In accomplice liability cases, the active and passive abuser must be clearly identified, and there must be usable evidence of the timing, manner, and extent of the injuries inflicted and that the passive abuser had or should have had knowledge of the active abuser’s conduct.

In the New York case of People v. Wong, this very issue was raised on appeal following a conviction of both parents of child abuse.

The New York Court of Appeals reversed both convictions with this statement:

We are duty-bound to reverse these two defendants’ convictions because the alternative – incarcerating both individuals for a crime of which only one is demonstrably culpable – is an unacceptable option in a system that is based on personal accountability and presumes each accused to be innocent until proven otherwise.

Sidebar 1 – The Dangers of a State Grant of Immunity to One Parent to Testify Against the Other

Under Colorado law, the prosecutor has the right to compel one parent to testify against the other through the use of a grant of immunity to secure the required eyewitness testimony. But there are enormous risks the prosecutor’s choice of which party to immunize is particularly vulnerable to error.

When the district attorney is not completely certain which of the respective parties (parents in this instance) caused the child’s injuries, guessing incorrectly and granting immunity to compel testimony could mean the guilty or more culpable party could go free.

The prosecutor has a fifty percent chance of being wrong and if both parties are equally responsible, (under and aiding and abetting theory), one of the two parties is never held responsible. This risk is rarely taken and in the absence of strong evidence identifying one of the two parents as the perpetrator, the case is usually never filed, or if it is filed, it is dismissed for failure of proof.

Sidebar 2: No Right to Marital Privilege – No Spousal Confidentiality in Colorado in Child Abuse Cases

It may be surprising to many that the Colorado child abuse statute, which has as one of the purposes of the law to establish “the duty of one parent to protect the child from the other parent” that the “ the shield of confidentially” that usually protects one spouse from being compelled to testify by the other, has been removed as a matter of law.

Section 18-6-401(3) provides that:

The statutory privilege between patient and physician and between husband and wife shall not be available for excluding or refusing testimony in any prosecution for a violation of this section.

This law suspends the confidential communications privilege between legally married spouses in proceedings involving child abuse.

Summary and Conclusion -Understanding Colorado’s Child Abuse Laws Can Be Difficult – 18-6-401

The people most likely to be falsely accused of child abuse are the child’s parents but alleged child abusers can be anyone responsible for the care of a child such as childcare providers, teachers, or foster parents.

A false accusation of child abuse is one of the most serious offenses the state can allege against a parent. Society places a “bright-line standard” in the law for the protection of children. Unfortunately, because of our society’s love of children, there is sometimes a less than thorough and objective investigation into an allegation of child abuse that can result in charges filed based on the weakest of evidence.

When a legal system is manipulated into “protecting” a child from an innocent parent, such a case can ruin the lives of all involved, most importantly the child.

The impact of even an accusation of the heinous crime of child abuse can follow the innocent parent for the rest of his or her life.

This brief article was intended to help the reader to understand some of the more complex issues facing parents accused of child abuse in Colorado by first understanding the components and the nature of the crime itself.

A person charged with a crime requires the guiding hand of counsel at every step in the proceedings against him. Without it, though he be not guilty, he faces the danger of conviction because he does not know how to establish his innocence.”

United States Supreme Court – Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45, 69 (1932)

If you found any information I have provided on this web page article helpful please share it with others over social media so they may also find it. Thank you.

Never stop fighting – never stop believing in yourself and your right to due process of law.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: H. Michael Steinberg – Email The Author at hmsteinberg@hotmail.com – A Denver Colorado Criminal Defense Lawyer – or call his office at 303-627-7777 during business hours – or call his cell if you cannot wait and need his immediate assistance – 720-220-2277. Attorney H. Michael Steinberg is passionate about criminal defense. His extensive knowledge of Colorado Criminal Law and his 42 plus years of experience in the courtrooms of Colorado may give him the edge you need to properly defend your case.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: H. Michael Steinberg – Email The Author at hmsteinberg@hotmail.com – A Denver Colorado Criminal Defense Lawyer – or call his office at 303-627-7777 during business hours – or call his cell if you cannot wait and need his immediate assistance – 720-220-2277. Attorney H. Michael Steinberg is passionate about criminal defense. His extensive knowledge of Colorado Criminal Law and his 42 plus years of experience in the courtrooms of Colorado may give him the edge you need to properly defend your case.

Colorado Criminal Lawyer Blog

Colorado Criminal Lawyer Blog